Calvin's Institutes, bk. 3, ch. 10, sec. 6

". . . if we follow the traces of our own actions to their source, they intimate some understanding of the good life." -Matthew B. Crawford, motorcycle mechanic and academic

Monday, December 31, 2012

No Task So Sordid and Base

"A man of obscure station will lead a private life ungrudgingly so as not to leave the rank in which he has been placed by God. Again, it will be no slight relief from cares, labors, troubles, and other burdens for a man to know that God is his guide in all these things. The magistrate will discharge his functions more willingly; the head of the household will confine himself to his duty; each man will bear and swallow the discomforts, vexations, weariness, and anxieties in his way of life, when he has been persuaded that the burden was laid upon him by God. From this will arise also a singular consolation: that no task will be so sordid and base, provided you obey your calling in it, that it will not shine and be reckoned very precious in God's sight."

Saturday, December 29, 2012

Indispensable, the Biblical Conversation

"When people converse in a desperate situation, they are usually looking for hope. I believe that the Bible as a whole tends toward a tenacious but severely chastened hope. That finely balanced disposition rests on faith in God, but it reflects also the experience of land loss and the equally bitter experience of a people's self-recognition. In its character of hopefulness tempered by sad experience, the biblical conversation is a good match for our contemporary agrarian conversation, and a resource indispensable for enriching it."

Artisans Possessed of Wisdom

". . . 'And every woman wise of heart spun with her hands, and they brought the spinning, the blue and the purple and the scarlet, and the fine linen. . . . And Moses called Bezalel and Oholiab and everyone wise of heart, in whose heart God had put wisdom, all whose heart elevated them, to enter into the craftwork, to do it' (Exodus 35:25; 36:2; cf. 36:1,4).

It is appropriate to speak of the artisans as possessed of wisdom (and not just 'skill'), because the biblical writers share the understanding common to most traditional societies that the active form of wisdom is good work. Wisdom does not consist only in sound intellectual work; any activity that stands in a consistently productive relationship to the material world and nurtures the creative imagination qualifies as wise. The modern failure to honor physical work that is skilled but nonetheless 'ordinary' has resulted in the devaluation and humiliation of countless workers. Moreover, probably everyone on the planet is now affected, directly or indirectly, by industrial society's widespread disconnection from the physical world as a source of meaning and therefore focus of love."

It is appropriate to speak of the artisans as possessed of wisdom (and not just 'skill'), because the biblical writers share the understanding common to most traditional societies that the active form of wisdom is good work. Wisdom does not consist only in sound intellectual work; any activity that stands in a consistently productive relationship to the material world and nurtures the creative imagination qualifies as wise. The modern failure to honor physical work that is skilled but nonetheless 'ordinary' has resulted in the devaluation and humiliation of countless workers. Moreover, probably everyone on the planet is now affected, directly or indirectly, by industrial society's widespread disconnection from the physical world as a source of meaning and therefore focus of love."

Creative Agrarian Work: Cities, Suburbs and Race

"Some of the more creative agrarian work now being done is the protection of farmlands, and especially smaller farms, so that they do not become housing developments or second homes for urbanites with ready cash. At the same time, those who live in cities and suburbs must have a stake in the countryside that is both emotional and economic. The common biblical metaphor for the relationship between a city and its surrounding villages is that of a mother and her daughters (Num. 21:25; Josh. 15:45, 57, etc.); it connotes mutual belonging, affection, benefit, and need. That image should be embraced and promoted by those of us who, farmers or not, sense the 'deadly impermanence' of the global economy and seek sustenance outside it, for ourselves, and even more, for our children.

Transformed models of land ownership are being developed and implemented, including regulations and easements on private property that restrict some form of alteration and protect wetlands, forests, and arable land. Some family farms are being purchased by public and nonprofit conservation trusts operating at various levels: national (the American Farmland Trust), state and provincial (e.g., Main Farmland Trust, Ontario Farmland Trust), county and regional. The suburban town of Weston, Massachusetts, ten miles from Boston, has developed an educational farm on town-owned conservation land. The town contracts with a nonprofit community farming organization to run the farm, and local youth work in its various commercial enterprises (firewood and timber, maple syrup, organic flowers, fruits and vegetables), gaining both employment and skills training.

Moreover, farmers' markets and membership farms (Community Supported Agriculture, 'CSAs') are now enabling small farmers in exurban areas to stay on the land, while urbanites and suburbanites have the pleasure and tangible benefits of investing in their 'breadbasket' communities. In dramatic contract to the general statistics for family farm collapse in the United States, the number of small farms that sell directly to their neighbors increased by 20 percent between 2001 and 2007. The number of farmers' markets increased from 340 in 1970 to 3,700 in 2004. Anathoth Community Garden in Cedar Grove, North Carolina, is a CSA that demonstrates another potential benefit of community farming, namely, the healing of rifts along economic, ethnic, and racial lines. In this small rural community, such rifts had led to a murder, apparently provoked by racism. Out of the community's agitation and grief came a vision: A lifelong member of the community, a woman whose grandfather had been born into slavery, offered five acres of land to Cedar Grove United Methodist - once known as 'the rich white church' - for the purpose of planting a community vegetable garden. Now Asians, Mexicans, Hondurans, African and European Americans, Christians and non-Christians, poor and relatively rich, work that land together, and have weekly dinners on the ground. The older farmers contribute their local knowledge and their manure - things that no one had seemed to value before. The food goes to those who need it most; some need it very badly. A community that a few years ago was riven by fear is now growing in trust and joy. in biblical terms, the people of Cedar Grove are reclaiming their nahala, which is, in its widest sense, the means of livelihood and blessing in community bestowed and received as the gift of God."

Transformed models of land ownership are being developed and implemented, including regulations and easements on private property that restrict some form of alteration and protect wetlands, forests, and arable land. Some family farms are being purchased by public and nonprofit conservation trusts operating at various levels: national (the American Farmland Trust), state and provincial (e.g., Main Farmland Trust, Ontario Farmland Trust), county and regional. The suburban town of Weston, Massachusetts, ten miles from Boston, has developed an educational farm on town-owned conservation land. The town contracts with a nonprofit community farming organization to run the farm, and local youth work in its various commercial enterprises (firewood and timber, maple syrup, organic flowers, fruits and vegetables), gaining both employment and skills training.

Moreover, farmers' markets and membership farms (Community Supported Agriculture, 'CSAs') are now enabling small farmers in exurban areas to stay on the land, while urbanites and suburbanites have the pleasure and tangible benefits of investing in their 'breadbasket' communities. In dramatic contract to the general statistics for family farm collapse in the United States, the number of small farms that sell directly to their neighbors increased by 20 percent between 2001 and 2007. The number of farmers' markets increased from 340 in 1970 to 3,700 in 2004. Anathoth Community Garden in Cedar Grove, North Carolina, is a CSA that demonstrates another potential benefit of community farming, namely, the healing of rifts along economic, ethnic, and racial lines. In this small rural community, such rifts had led to a murder, apparently provoked by racism. Out of the community's agitation and grief came a vision: A lifelong member of the community, a woman whose grandfather had been born into slavery, offered five acres of land to Cedar Grove United Methodist - once known as 'the rich white church' - for the purpose of planting a community vegetable garden. Now Asians, Mexicans, Hondurans, African and European Americans, Christians and non-Christians, poor and relatively rich, work that land together, and have weekly dinners on the ground. The older farmers contribute their local knowledge and their manure - things that no one had seemed to value before. The food goes to those who need it most; some need it very badly. A community that a few years ago was riven by fear is now growing in trust and joy. in biblical terms, the people of Cedar Grove are reclaiming their nahala, which is, in its widest sense, the means of livelihood and blessing in community bestowed and received as the gift of God."

Scripture, Culture, and Agriculture, pp. 117-9

Friday, December 28, 2012

Industrial Agriculture More Efficient, . . . Really?

"The standard rationale for industrial agriculture, energetically promoted by the multinationals that profit from it, is that it is more efficient; it can feed the world and do so cheaply. Yet, in fact, small farms everywhere, in North America and also in the Third World, are more productive than large ones, for multiple reasons. An industrial soybean farm may produce more beans per acre, but the small-farm, planted with six to twelve different crops, has a much higher total yield, both in food quantity and in market value. Plants do favors for each other. In agrarian cultures in Mexico and northern Central America, farmers have traditionally interplanted 'the three sisters': corn, beans, and squash. The corn provides trellises for the beans, the squash leaves discourage weeds and retard evaporation, and the beans fix nitrogen that enhance soil fertility for all three crops. Polycropping and even the planting of diverse varieties within a species also help with pest control; the different crops create more habitational niches for beneficial organisms, and harmful organisms are unlikely to have an equally devastating effect on every crop. Small farmers often integrate crops and livestock, rotating pasture and planted fields in a single system of recycled biomass and nutrients.

The difference in productivity between small farms and industrial farms is not slight. In every country for which data is available, smaller farms are shown to be 200 to 1,000 percent more productive per unit area. Moreover, small farming is more productive because the quality and even the quantity of labor and land care is higher when workers invest themselves in their own farm and community. Farmers who expect their families to have a future on the land do not willingly mortgage that future by robbing soil and water of their long-term health. Productivity and cost-effectiveness are durative qualities, although the short-term 'success' of agribusiness depends on ignoring the truth.

Small farms also generate more prosperity for nearby rural towns, where farmers buy supplies and in turn find markets for their produce. . . ."

The difference in productivity between small farms and industrial farms is not slight. In every country for which data is available, smaller farms are shown to be 200 to 1,000 percent more productive per unit area. Moreover, small farming is more productive because the quality and even the quantity of labor and land care is higher when workers invest themselves in their own farm and community. Farmers who expect their families to have a future on the land do not willingly mortgage that future by robbing soil and water of their long-term health. Productivity and cost-effectiveness are durative qualities, although the short-term 'success' of agribusiness depends on ignoring the truth.

Small farms also generate more prosperity for nearby rural towns, where farmers buy supplies and in turn find markets for their produce. . . ."

Scripture, Culture, and Agriculture, p. 103-4

Thursday, December 27, 2012

Not Caring for Creation, a Covenantal Crisis

"In Britain, a 1998 report to the Government's Joint Nature Conservation Committee revealed that in twenty-five years habitat loss and agricultural biocides had drastically reduced the populations of several of the (formerly) most common birds - for example, tree sparrows, by 95 percent; grey partridges, by 86 percent; and turtle doves, by 69 percent. With 75 percent of marine fisheries either fished to capacity or overfished, perhaps 30 percent of fish species are threatened. Our record makes an eerily exact mockery of God's commandment to the living creatures on the fifth day; 'Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the waters in the seas - and the birds, let them multiply on the earth' (Gen. 1:22). Read in light of the current data, it would seem that the mockery begins already with the parallel commandment addressed to the humans on the sixth day: . . ."

"Suffering, disease, and wasteful death for so-called domesticated animals is also a large part of the cost of our eating habits and food production system. The abandonment of long-standing practices of animal husbandry in favor of 'concentrated animal feeding operations' (CAFOs) has led to the emergence of new epidemics such as BSE ('mad cow disease'), which is communicable to humans; moreover, old diseases have spread to an unprecedented extent. 'Plague' was the description applied to Europe's 2001 outbreak of food-and-mouth disease, a form of nonlethal animal flu that is preventable by vaccine and treatable by ordinary veterinary care. In this case, however, ten million animals were destroyed, millions of them not infected, because their market value had plummeted and trade policies demanded it. Colin Tudge observes the irony that hygiene laws designed to maintain food in a state of asepsis 'are superimposed on a system of food production and distribution that seems specifically intended to generate and spread infection, or at least could hardly do the job better if it had been.'

But infectious disease is only the tip of the iceberg of suffering that is built into industrial systems of animal confinement and slaughter. Eighty million of the 95 million hogs slaughtered each year in the United States are the product of CAFOs. The scale is gigantic: 60 percent of the hogs are processed 'from birth to bacon' by just four companies. They never feel soil or sunshine, and rarely the touch of a human hand. A 500-pound sow spends an adult lifetime - measured in terms of litters and terminated after the eighth, if she survives that long - in a metal crate seven feet long and twenty-two inches wide, covered with sores, her swollen legs planted in urine and excrement. On the kill-floor at Smithfield's Tar Heel plants, hogs are stunned, slashed, hoisted and scalded at the rate of 2,000 per hour. When the four-pronged stunner misses its mark, then the flailing animal may be dropped alive into the scalding tank. 'The electrocutors, stabbers, and carvers who work on the floor wear earplugs to muffle the screaming.' Indeed, animal suffering and human suffering is intertwined; the Tar Heel plant has a 100 percent annual turnover among its five thousand employees, most of them immigrants. The uncompromising stricture found in Leviticus on the slaughter of animals might serve as a commentary on our current practices: 'If anyone from the house of Israel who slaughters an ox or a sheep or a goat in the camp or who slaughters it outside the camp does not bring it to the entrance of the Tent of Meeting, to offer to YHWH before the Tabernacle of YHWH, as blood it should be accounted to that man; he has shed blood. And that man shall be cut off from the midst of his people' (Lev. 17:3-4).

The cost of our eating is paid even in the distortion of agriculture itself, to service the meat and dairy industries. Beef cattle now consume half the world's wheat, most if its corn (a grain they do not naturally eat), and almost all of its soybeans. In turn, the agricultural industry is the largest consumer of water in North America. In addition, to these extractions from the earth, the meat industry is responsible for dangerous inputs, including massive direct pollution of soil, water, and air from intensive 'livestock units.' In California's Central Valley, 1,600 dairies produce more effluents than a city of 21 million people. In 1997, the Senate and Agriculture Committee reported that the total manure waste produced by U.S. animal industries was 1.3 billion tons: 130 times the amount of human waste processed in the nation. Workers inside the factories and also nearby residents suffer high rates of respiratory and sinus problems, as well as nausea and diarrhea.

How Israel eats is a covenantal concern. From the perspective of Leviticus, whether Israel eats at all is in the long term a function of covenant faithfulness practice among three parties: God, land, and people."

"Suffering, disease, and wasteful death for so-called domesticated animals is also a large part of the cost of our eating habits and food production system. The abandonment of long-standing practices of animal husbandry in favor of 'concentrated animal feeding operations' (CAFOs) has led to the emergence of new epidemics such as BSE ('mad cow disease'), which is communicable to humans; moreover, old diseases have spread to an unprecedented extent. 'Plague' was the description applied to Europe's 2001 outbreak of food-and-mouth disease, a form of nonlethal animal flu that is preventable by vaccine and treatable by ordinary veterinary care. In this case, however, ten million animals were destroyed, millions of them not infected, because their market value had plummeted and trade policies demanded it. Colin Tudge observes the irony that hygiene laws designed to maintain food in a state of asepsis 'are superimposed on a system of food production and distribution that seems specifically intended to generate and spread infection, or at least could hardly do the job better if it had been.'

But infectious disease is only the tip of the iceberg of suffering that is built into industrial systems of animal confinement and slaughter. Eighty million of the 95 million hogs slaughtered each year in the United States are the product of CAFOs. The scale is gigantic: 60 percent of the hogs are processed 'from birth to bacon' by just four companies. They never feel soil or sunshine, and rarely the touch of a human hand. A 500-pound sow spends an adult lifetime - measured in terms of litters and terminated after the eighth, if she survives that long - in a metal crate seven feet long and twenty-two inches wide, covered with sores, her swollen legs planted in urine and excrement. On the kill-floor at Smithfield's Tar Heel plants, hogs are stunned, slashed, hoisted and scalded at the rate of 2,000 per hour. When the four-pronged stunner misses its mark, then the flailing animal may be dropped alive into the scalding tank. 'The electrocutors, stabbers, and carvers who work on the floor wear earplugs to muffle the screaming.' Indeed, animal suffering and human suffering is intertwined; the Tar Heel plant has a 100 percent annual turnover among its five thousand employees, most of them immigrants. The uncompromising stricture found in Leviticus on the slaughter of animals might serve as a commentary on our current practices: 'If anyone from the house of Israel who slaughters an ox or a sheep or a goat in the camp or who slaughters it outside the camp does not bring it to the entrance of the Tent of Meeting, to offer to YHWH before the Tabernacle of YHWH, as blood it should be accounted to that man; he has shed blood. And that man shall be cut off from the midst of his people' (Lev. 17:3-4).

The cost of our eating is paid even in the distortion of agriculture itself, to service the meat and dairy industries. Beef cattle now consume half the world's wheat, most if its corn (a grain they do not naturally eat), and almost all of its soybeans. In turn, the agricultural industry is the largest consumer of water in North America. In addition, to these extractions from the earth, the meat industry is responsible for dangerous inputs, including massive direct pollution of soil, water, and air from intensive 'livestock units.' In California's Central Valley, 1,600 dairies produce more effluents than a city of 21 million people. In 1997, the Senate and Agriculture Committee reported that the total manure waste produced by U.S. animal industries was 1.3 billion tons: 130 times the amount of human waste processed in the nation. Workers inside the factories and also nearby residents suffer high rates of respiratory and sinus problems, as well as nausea and diarrhea.

How Israel eats is a covenantal concern. From the perspective of Leviticus, whether Israel eats at all is in the long term a function of covenant faithfulness practice among three parties: God, land, and people."

Scripture, Culture, and Agriculture, p. 98-9

Agrarianism

"Agrarianism is more than a set of farming practices, more than an attitude toward food production and consumption, although both of these are central to it. Agrarianism is nothing less than a comprehensive philosophy and practice - that is, a culture - of preservation. Agrarians are committed to preserving both communities and the material means of life, to cultivating practices that ensure that the essential means of life suffice for all members of the present generation and are not diminished for those who come after. Agrarianism in this sense is, and has nearly always been, a marginal culture, existing at the edge or under the domination of a larger culture whose ideology, social system, and economy are fundamentally different. So agrarian writers, both ancient and modern, always speak with a vivid awareness of the threat posed by the culture of the powerful."

Monday, December 24, 2012

Joy . . . Blessings Far as the Curse is Found!

I've been thinking a lot as of late about the expansive significance of the coming of Christ on a cosmic and global scale; I get to talk a little about how God has been leading me here tonight at Grace Chapel's 5pm Christmas Eve Service (all are invited!)

I recently came across this interview with Old Testament professor Dr. Ellen F. Davis of Duke Divinity School. Davis, being a Bible scholar and heavily influenced by the writings of Wendell Berry, . . . I found her reflections to be extremely helpful, disturbing, encouraging and thought-provoking all at the same time. Also, recently, I've been working through Davis' book:

"From a Biblical perspective, the covenant is not purely a two-way relationship between human beings and God. The covenant is a three-way relationship, . . . thinking about the aftermath of the flood story in Genesis when God makes a covenant with kol basar, "all flesh," . . . all of the nonhuman creatures. . ." -Ellen F. Davis

"Eating is. . . the primary ecological act. Eating is the thing that most regularly connects us to the rest of the created order." -Ellen F. Davis

"We're in a system that does not have a long future. The good news. . . is that we will not be farming the way we are farming now fifty years from now. The bad news is we won't have the resources to do it. More than 50% of the topsoil in Iowa has been eroded; . . . and similar in other places. Our erosion rates far outpace replacement rates. . . ." -Ellen F. Davis

"Anyone who gardens understands that the earth is not an 'it' upon which we act at our will; it's a creature with whom we have an opportunity to have a fruitful relationship." -Ellen F. Davis

Monday, December 17, 2012

In Honor and Memory of Madeleine Hsu, 6

I am simply overwhelmed at the thought of the Newtown school shootings; Tanya cried this morning and I cry now as I write. I don't even know where to start with my sadness, but since this precious girl shares my namesake (though not related to me), I'll start by seeking to honor her here.

"Those who wish to see Him must see Him in the poor, the hungry, and the hurt, the wordless creatures, the groaning and travailing beautiful world.... We are too tightly tangled together to be able to separate ourselves from one another either by good or by evil. We all are involved in all and any good, and in all and any evil. For any sin, we all suffer. That is why our suffering is endless. It is why God grieves and Christ's wounds are still bleeding" (Jayber Crow, p. 295).

"Those who wish to see Him must see Him in the poor, the hungry, and the hurt, the wordless creatures, the groaning and travailing beautiful world.... We are too tightly tangled together to be able to separate ourselves from one another either by good or by evil. We all are involved in all and any good, and in all and any evil. For any sin, we all suffer. That is why our suffering is endless. It is why God grieves and Christ's wounds are still bleeding" (Jayber Crow, p. 295).

Friday, December 14, 2012

Vocations Never End While Occupations Do

"A friend once said to Winston Churchill that there was something to be said for being a retired Roman Emperor. 'Why retired?' Churchill growled. 'There's nothing to be said for retiring from anything.' As followers of Christ we are called to be before we are called to do and our calling both to be and do is fulfilled only in being called to him. So calling should not only precede career but outlast it too. Vocations never end, even when occupations do. We may retire from our jobs but never from our calling. We may at times be unemployed, but no one ever becomes uncalled."

The Call, p. 230

Thursday, December 13, 2012

The Distortion of Manifest Destiny as Calling

". . . America's 'Manifest Destiny,' or more broadly America's sense of exceptionalism, can be traced to various roots, geographical and economic, but the deepest root is theological. The English Puritans saw their revolution as 'God's own Cause' and their Commonwealth (in poet Andrew Marvell's words) as 'the darling of heaven.' So when their revolution failed and they migrated from the Egypt of England to the Canaan of New England, they transferred the sense of destiny. They were 'the Lord's first born,' entrusted with a 'pious errand into the wilderness.' In short, with America destiny preceded discovery.

To be fair to the Puritans, they neither coined the term manifest destiny nor believed in the idea. They believed that God had a providential purpose for all nations, including the United States. It was not for the United States alone. The term manifest destiny was first used in 1845 by John L. Sullivan, the editor of Democratic Review. It was a secular, nationalistic distortion of calling that needs to be challenged in a nation as much as in an individual."

To be fair to the Puritans, they neither coined the term manifest destiny nor believed in the idea. They believed that God had a providential purpose for all nations, including the United States. It was not for the United States alone. The term manifest destiny was first used in 1845 by John L. Sullivan, the editor of Democratic Review. It was a secular, nationalistic distortion of calling that needs to be challenged in a nation as much as in an individual."

The Call, p. 115

Saturday, December 8, 2012

Faith, the Only Certainty

"Both faith and doubt have their proper roles in the whole enterprise of knowing, but faith is primary and doubt is secondary because rational doubt depends upon beliefs that sustain our doubt. The ideal that modernity, following Descartes, has set before itself, namely, the ideal of a kind of certainty that admits no possibility of doubt, is leading us into skepticism and nihilism. The universe is not provided with a spectator's gallery in which we can survey the total scene without being personally involved. True knowledge of reality is available only to the one who is personally committed to the truth already grasped. Knowing cannot be severed from living and acting, for we cannot know the truth unless we seek it with love and unless our love commits us to action. Faith is the only certainty because faith involves personal commitment. The point has often been made that there is a distinction between 'I believe that . . .' and 'I believe in. . . .' But faith holds both together; to separate them is to deny oneself access to truth.

The confidence proper to a Christian is not the confidence of one who claims possession of demonstrable and indubitable knowledge. It is the confidence of one who had heard and answered the call that comes from the God through whom and for whom all things were made: 'Follow me.'"

The confidence proper to a Christian is not the confidence of one who claims possession of demonstrable and indubitable knowledge. It is the confidence of one who had heard and answered the call that comes from the God through whom and for whom all things were made: 'Follow me.'"

Proper Confidence, p. 105

Saved from Two Dangers

"If we allow the Bible to be that which we attend to above all else, we will be saved from two dangers: The first is the danger of the closed mind. The Bible leaves an enormous space open for exploration. If our central commitment is to Jesus, who is the Word of God incarnate in our history, we shall know that in following him we have the clue to the true understanding of all that is, seen and unseen, known and yet to be discovered. We shall therefore be confident explorers. The second danger is the danger of the mind open at both ends, the mind which is prepared to entertain anything but has a firm hold of nothing. We shall be saved from the clueless wandering which sometimes takes to itself the name of pilgrimage. A pilgrim is one who turns his back on some familiar things and sets his face in the direction of the desired goal. The Christian is called to be a pilgrim, a learner to the end of her days. But she knows the Way."

Proper Confidence, pp. 91-2

Proper Confidence, by Lesslie Newbigin

Long-time missionary to South India and General Secretary of the World Council of Churches, Lesslie Newbigin, explores the Enlightenment project's dubious quest for certainty, resulting division between "facts" and "values" embodied in the enterprise of Newtonian physics and the modern assumption in the world of academia as well as "common thought" that there are certain phenomena that are "objective and reliable" (i.e., science and mathematics) and others (i.e., religion and the social sciences) that are "subjective" and merely open to a variety of interpretations and meanings. In what sense has much of modern thought remained enslaved and mindlessly bought into such a view of the world? And in what sense have even the churches that have considered themselves to be most faithful to God and the Bible, lacked such cultural and historical awareness, so as to have remained "whippin' boys" for Master Enlightenment? What if instead we understood the quest for certainty as one that begins with the assumption of faith and belonging (against the "secular mind") and one that is grounded in "grace received through faith" (against the arrogance of much of modern Christianity)? Instead of doubt being the starting point on the quest for knowledge, what if faith in a larger story was the starting point from where we evaluate, critique, question and even take up the freedom to doubt along the way? Here are some excerpts from Newbigin's Proper Confidence:

"Scientists, and indeed all serious scholars, speak often of the love of truth. But can love be finally satisfied with an impersonal 'something'? Have we, perhaps, failed to draw out the full meaning of the words spoken by the apostle Paul to the scholars and debaters of Athens when he said that 'the God who made the world and everything in it . . . . did this so that men would seek him and perhaps reach out for him and find him, though he is not far from each one of us" (Acts 17:24,27)?'" (p. 63).

"The fundamentalist critique of liberal theology must be taken seriously. But fundamentalists do a disservice to the gospel when, as sometimes happens, they adopt a style of certainty more in the tradition of Descartes than in the truly evangelical spirit. This can show itself in several familiar ways. Sometimes it is an anxiety about the threat that new discoveries in science may pose to Christian faith – an anxiety that betrays a lack of total confidence in the central truth of the gospel that Jesus is the Word made flesh. Sometimes it leads to a refusal to reconsider long-held beliefs in the light of fresh reflection on the witness of Scripture. One may contrast this with the truly liberal spirit shown by the Jews of Berea, for when confronted by the revolutionary message of the apostle, they did not simply reject it but 'examined the Scriptures every day to see if what Paul said was true' (Acts 17:11). And it can manifest itself in a claim for the objective truth of the Christian message that seems to depend on the acceptance of the false dualism of Enlightenment thought. Insofar as the word 'objective' is used as a synonym for 'really true,' one must of course accept it unreservedly. But, it seems to me, its use in the context of modern thinking can lead to the false impression that the Christian faith is a matter of demonstrable fact rather than a matter of grace received in faith. Perhaps liberals would be more ready to listen to the very serious question put to them by fundamentalists if the latter were more manifestly speaking as those who must think, as they must live, as debtors of grace" (pp. 70-1).

"The business of the church is to tell and to embody a story, the story of God's mighty acts in creation and redemption and of God's promises concerning what will be in the end. The church affirms the truth of this story by celebrating it, interpreting it, and enacting it in the life of the contemporary world. It has no other way of affirming its truth. If it supposes that its truth can be authenticated by reference to some allegedly more reliable truth claim, such as those offered by the philosophy of religion, then it has implicitly denied the truth by which it lives" (p. 76).

"Even in the darkest hours, signs of the divine presence shine with a brightness that cannot be hidden. And the story that the church tells continues to exercise its power both to correct and reform the church and to convince and convert the world. And however grievous the apostasy of the church may be, it remains that God has entrusted to it this story and that there is no other body that will tell it. From age to age, the church lives under the authority of the story that the Bible tells, interpreted ever anew to new generations and new cultures by the continued leading of the Holy Spirit who alone makes possible the confession that Jesus is Savior and Lord. God's sovereignty is that of God's grace. It is as savior that God is Lord. It is as the one who overcomes our alienation from the truth that God reveals the truth. We are not, as we like to think, naturally lovers of the truth. It has become possible for us to know God and to speak confidently of God only because the beloved Son who knows the Father has taken our place in our estrangement form God and has made it possible to come to a true knowledge of God through him. So the revelation of God given to us in him is not a matter of coercive demonstration but of grace, of a love that forgives and invites. That reality of grace governs both the confidence we have in speaking of God and the manner in which we must commend the gospel to others" (p. 78).

"Scientists, and indeed all serious scholars, speak often of the love of truth. But can love be finally satisfied with an impersonal 'something'? Have we, perhaps, failed to draw out the full meaning of the words spoken by the apostle Paul to the scholars and debaters of Athens when he said that 'the God who made the world and everything in it . . . . did this so that men would seek him and perhaps reach out for him and find him, though he is not far from each one of us" (Acts 17:24,27)?'" (p. 63).

"The fundamentalist critique of liberal theology must be taken seriously. But fundamentalists do a disservice to the gospel when, as sometimes happens, they adopt a style of certainty more in the tradition of Descartes than in the truly evangelical spirit. This can show itself in several familiar ways. Sometimes it is an anxiety about the threat that new discoveries in science may pose to Christian faith – an anxiety that betrays a lack of total confidence in the central truth of the gospel that Jesus is the Word made flesh. Sometimes it leads to a refusal to reconsider long-held beliefs in the light of fresh reflection on the witness of Scripture. One may contrast this with the truly liberal spirit shown by the Jews of Berea, for when confronted by the revolutionary message of the apostle, they did not simply reject it but 'examined the Scriptures every day to see if what Paul said was true' (Acts 17:11). And it can manifest itself in a claim for the objective truth of the Christian message that seems to depend on the acceptance of the false dualism of Enlightenment thought. Insofar as the word 'objective' is used as a synonym for 'really true,' one must of course accept it unreservedly. But, it seems to me, its use in the context of modern thinking can lead to the false impression that the Christian faith is a matter of demonstrable fact rather than a matter of grace received in faith. Perhaps liberals would be more ready to listen to the very serious question put to them by fundamentalists if the latter were more manifestly speaking as those who must think, as they must live, as debtors of grace" (pp. 70-1).

"The business of the church is to tell and to embody a story, the story of God's mighty acts in creation and redemption and of God's promises concerning what will be in the end. The church affirms the truth of this story by celebrating it, interpreting it, and enacting it in the life of the contemporary world. It has no other way of affirming its truth. If it supposes that its truth can be authenticated by reference to some allegedly more reliable truth claim, such as those offered by the philosophy of religion, then it has implicitly denied the truth by which it lives" (p. 76).

"Even in the darkest hours, signs of the divine presence shine with a brightness that cannot be hidden. And the story that the church tells continues to exercise its power both to correct and reform the church and to convince and convert the world. And however grievous the apostasy of the church may be, it remains that God has entrusted to it this story and that there is no other body that will tell it. From age to age, the church lives under the authority of the story that the Bible tells, interpreted ever anew to new generations and new cultures by the continued leading of the Holy Spirit who alone makes possible the confession that Jesus is Savior and Lord. God's sovereignty is that of God's grace. It is as savior that God is Lord. It is as the one who overcomes our alienation from the truth that God reveals the truth. We are not, as we like to think, naturally lovers of the truth. It has become possible for us to know God and to speak confidently of God only because the beloved Son who knows the Father has taken our place in our estrangement form God and has made it possible to come to a true knowledge of God through him. So the revelation of God given to us in him is not a matter of coercive demonstration but of grace, of a love that forgives and invites. That reality of grace governs both the confidence we have in speaking of God and the manner in which we must commend the gospel to others" (p. 78).

Friday, December 7, 2012

The Table

Whether Sally Lloyd-Jones enjoying a food retreat at The Laity Lodge or my good friend Ingrid Kutsch reflecting on the good gifts of a wonderful hospitality she received in a visit back home to Germany, food is cherished and honored among my network of friends. My good friend Jonathan Gregory was "teaching" another good friend Ben Loos how to make homemade pizza and Jonathan wrote up the wonderful little excerpt below.

http://www.laitylodge.org/artists-speakers/sally-lloyd-jones-8968/

http://www.ibkimage.com/2012/10/19/the-gifts-of-the-table/

http://www.laitylodge.org/artists-speakers/sally-lloyd-jones-8968/

http://www.ibkimage.com/2012/10/19/the-gifts-of-the-table/

Cooking is a Language, by Jonathan Gregory

We might say that cooking is a language, with a vocabulary and grammar. A plenteous, over-flowing tongue, proffering one with many things to say and ways to say them. A language with verb, nouns, and adjectives. A poet’s language, too.

Our verbs are the things we do bake, broil, braise, brown, sauté, boil, deglaze, chop, dice, mince, measure, mix. Some verbs are of the daily, ordinary sort we use over and over. Others are a special vocabulary used more rarely.

Our cooking nouns are the things we make. A few are so basic that they appear again and again as individual elements in many recipes. For example, yeast dough, batter, stock or broth, roux, and sautéed vegetables. Once we learn these nouns, we are enabled to use them in a variety of more interesting recipes such as cinnamon rolls, chocolate chip cookies, white chili, cream gravy, or broccoli beef.

Cooking language favors its adjectives. These are flavors and textures: aromatics, fats, acids, herbs, and spices. These create the character of the dish. Choice of adjectives make the difference between chili and marinara, between pot roast and beef bourguignon, between biscuits and scones.

Cooking encourages creative use of vocabulary and grammar. The poet-cook is the genius. But even he or she respects basic chemistries of the language that cannot be altered. He will always measure the leavening; she will keep milk from scorching. A cook will always be well compensated for respecting the absolutes.

The first noun we will learn—pizza—includes an introduction to several helpful parts of speech. We’ll learn kneading and baking as our verbs; yeast bread and pizza sauce as nouns; and use adjectives such as olive oil and cheese for the fats, garlic as our aromatic, and basil and oregano as our herb. And then anything else our muses suggest.

© 2012, Jonathan Gregory

Wednesday, December 5, 2012

Caring vs. Acedia

"Dorothy Sayers helps us understand the counterfeit passion that can drive our work. In her book Creed or Chaos?, Sayers addresses the traditional seven deadly sins, including acedia, which is often translated as 'sloth.' But as Sayers explains it, that is a misnomer, because laziness (the way we normally define sloth) is not the real nature of this condition. Acedia, she says, means a life driven by mere cost-benefit analysis of 'what's in it for me.' She writes, 'Acedia is the sin which believes in nothing, cares for nothing, enjoys nothing, loves nothing, find purpose in nothing, lives for nothing and only remains alive because there is nothing for which it will die. We have known it far too well for many years, the only thing perhaps we have not known about it is it is a mortal sin.'"

Tuesday, December 4, 2012

Diagnostic Questions Regarding Work

On p. 181 of his new book on work, Tim Keller asks the following diagnostic question, "Are you thinking about your work through the lenses of a Christian worldview?" and then Keller asks:

1) What's the story line of the culture in which I live and the field where I work? Who are the protagonists and antagonists?

2) What are the underlying assumptions about meaning, morality, origin, and destiny?

3) What are the idols? The hopes? The fears?

4) How does my particular profession retell this story line, and what part does the profession itself play in the story?

5) What parts of the dominant worldviews are basically in line with the gospel, so that I can agree with and align with them?

6) What parts of the dominant worldviews are irresolvable without Christ? Where, in other words, must I challenge my culture? How can Christ complete the story in a different way?

7) How do these stories affect both the form and the content of my work personally? How can I work not just with excellence but also with Christian distinctiveness in my work?

8) What opportunities are there in my profession for (a) serving individual people, (b) serving society at large, (c) serving my field of work, (d) modeling competence and excellence, and (e) witnessing to Christ?

1) What's the story line of the culture in which I live and the field where I work? Who are the protagonists and antagonists?

2) What are the underlying assumptions about meaning, morality, origin, and destiny?

3) What are the idols? The hopes? The fears?

4) How does my particular profession retell this story line, and what part does the profession itself play in the story?

5) What parts of the dominant worldviews are basically in line with the gospel, so that I can agree with and align with them?

6) What parts of the dominant worldviews are irresolvable without Christ? Where, in other words, must I challenge my culture? How can Christ complete the story in a different way?

7) How do these stories affect both the form and the content of my work personally? How can I work not just with excellence but also with Christian distinctiveness in my work?

8) What opportunities are there in my profession for (a) serving individual people, (b) serving society at large, (c) serving my field of work, (d) modeling competence and excellence, and (e) witnessing to Christ?

We Made the NY Times!

|

| Picture of Prairie Festival from the NY Times Article |

Monday, December 3, 2012

What is the Happy Life?

"Yale philosopher Nicholas Wolterstorff observes that modern culture defines the happy life as a life that is 'going well'–full of experiential pleasure–while to the ancients, the happy life meant the life that is lived well, with character, courage, humility, love and justice."

Tuesday, November 27, 2012

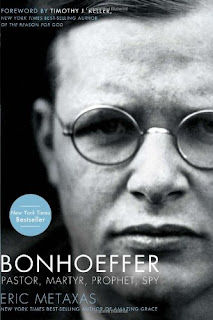

Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy

In Eric Metaxas' extensive biography of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Lutheran pastor, who was executed for his participation in a failed attempt to assassinate Hitler, we get some insight into the plot known by the name "Valkyrie." Of course at the time, Hitler was yet to be revealed as the absolute evil he turned out to be, so the international community viewed the assassination attempt with nearly universal contempt. Even the New York Times reported the assassination attempt as something one would not "normally expect within an officers' corps and a civilized government." The father of Bonhoeffer's fiancée, Henning von Tresckow, took his own life after the failed assassination attempt. Tresckow was involved in the plot and was afraid of revealing the names of others under torture. He spoke these words before taking his life:

The whole

world will vilify us now, but I am still totally convinced that we did the

right thing. Hitler is the archenemy not only of Germany but of the world.

When, in a few hours’ time, I go before God to account for what I have done and

left undone, I know I will be able to justify in good conscience what I did in

the struggle against Hitler. God promised Abraham that He would not destroy

Sodom if just ten righteous men could be found in the city, and so I hope for

our sake God will not destroy Germany. None of us can bewail his own death;

those who consented to join our circle put on the robe of Nessus. A human being’s

moral integrity begins when he is prepared to sacrifice his life for his

convictions. Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy, p. 487

There are certainly some challenging questions regarding Christian ethics in all this. However, in reading this excerpt, I primarily thought a lot of the writings of my doctoral mentor Steven Garber who has written about seeing with our hearts to take responsibility for the world as it is and as it should be. Henning von Tresckow certainly seemed to me to be one of these men, like Bonhoeffer, as have been others throughout history such as playwright and former president of Czechoslovakia and the former Czech Republic, Vaclav Havel, who famously wrote "the secret of man is the secret of his responsibility."

Every Good Endeavor, by Tim Keller

At the risk of offending some as I share this, I walked into the Grace Chapel office yesterday announcing to the GC Staff, "The Kingdom Has Come! Tim Keller has put out a book on vocation!" Some have jokingly asked me if I was envious that Keller beat me to the punch in writing a book on vocation. I respond, "please don't utter my name in the same breath as Tim Keller!" I would say that the two most influential voices in my ministry to this point have been Tim Keller and Wendell Berry. Well, so I'm off and running on Keller's book. Let me share some of the excerpts I've enjoyed so far:

The work-obsessed mind–as in our

Western culture–tends to look at everything in terms of efficiency, value, and

speed. But there must also be an ability to enjoy the most simple and ordinary

aspects of life, even ones that are not strictly useful, but just delightful.

Surprisingly, even the reputedly dour Reformer John Calvin agrees. In his

treatment of the Christian life, he warns against valuing things only for their

utility:

Did God create food only to

provide for necessity [nutrition] and not also for delight and good cheer? So

too the purpose of clothing apart from necessity [protection] was comeliness

and decency. In grasses, trees, and fruits, apart from their various uses,

there is beauty of appearance and pleasantness of fragrance. . . . Did he not,

in short, render many things attractive to us, apart from their necessary use?

In

other words, we are to look at everything and say something like:

All things bright and beautiful;

all creatures great and small

All things wise and wonderful–the

Lord God made them all.

(Every Good Endeavor, p. 41)

In Luther’s Large

Catechism, when he addresses the petition in the Lord’s Prayer asking God to

give us our “daily bread,” Luther says that “when you pray for ‘daily bread’

you are praying for everything that contributes to your having and enjoying

your daily bread. . . . You must open up and expand your thinking, so that it

reaches not only as far as the flour bin and baking oven but also out over the

broad fields, the farmlands, and the entire country that produces, processes,

and conveys to us our daily bread and all kinds of nourishment.” So how does

God “feed everything living thing” (Psalm 145:16) today? Isn’t it through the

farmer, the baker, the retailer, the website programmer, the truck driver, and

all who contribute to bring us food? Luther writes: God could easily give you

grand and fruit without your plowing and planting, but he does not want to do

so.”

(Every Good Endeavor, p. 70)

Even though, as Luther argues, all

work is objectively valuable to others, it will not be subjectively fulfilling

unless you consciously see and understand your work as calling to love your

neighbor. John Calvin wrote that “no task will be [seen as] so sordid and base,

provided you obey your calling in it, that it will not shine and be reckoned

very precious in God’s sight.” Notice that Calvin speaks of “obey[ing] your

calling in it”’ that is, consciously

seeing your job as God’s calling and offering the work to him. When you do

that, you can be sure that the splendor of God radiates through any task,

whether it is as commonplace as tilling a garden, or as rarefied as working on

the global trading floor of a bank. As Eric Liddell’s missionary father exhorts

him in Chariots of Fire, “You can

praise the Lord by peeling a spud, if you peel it to perfection.”

Your

daily work is ultimately an act of worship to the God who called and equipped

you to do it–no matter what kind of work it is. In the liner notes to his

masterpiece A Love Supreme, John

Coltrane says it beautifully:

This album is a humble offering to

Him. An attempt to say “THANK YOU GOD” through our work, even as we do in our

hearts and with our tongues. May He help and strengthen all men in every good

endeavor.

(Every Good Endeavor, p. 80)

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.jpg)